- Home

- Virginia Lloyd

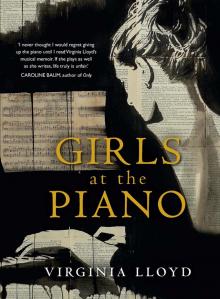

Girls at the Piano

Girls at the Piano Read online

‘I felt pulled toward my grandmother by what little I knew and an urgent desire to find other parallels between our experiences as musical girls. I wanted to explore how our experiences reflected those of other girls drawn from the pages of history and fiction who had sat at the piano over the course of its history. I came to believe that setting aside Alice’s mask of old age might help me to understand my own voyage around the piano—and help me to find my way back.’

‘Staring into the piano’s black mirror was like seeing into the future, glimpsing the girl I would become, the girl who could play the piano and understand the world around her through her fingertips, and let her hands speak for her when she could not.’

First published in 2018

Copyright © Virginia Lloyd 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Every effort has been made to trace the holders of copyright material.

If you have any information concerning copyright material in this book please contact the publishers at the address below.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone:(61 2) 8425 0100

Email:[email protected]

Web:www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76029 777 0

eISBN 978 1 76063 586 2

Internal design by Romina Panetta

Set by Bookhouse, Sydney

Cover design: Romina Panetta

Cover illustration: Loui Jover, Her Sonata, courtesy Saatchi Art

for Nate

CONTENTS

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

ENDNOTES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

From this I reach what I might call a philosophy; at any rate it is a constant idea of mine; that behind the cotton wool is hidden a pattern; that we—I mean all human beings—are connected with this; that the whole world is a work of art; that we are parts of the work of art. Hamlet or a Beethoven quartet is the truth about this vast mass that we call the world. But there is no Shakespeare, there is no Beethoven; certainly and emphatically there is no God; we are the words; we are the music; we are the thing itself.

Virginia Woolf, ‘A Sketch of the Past’

1

‘YOU’RE GOING TO HAVE TWO CHILDREN, a boy and a girl,’ the clairvoyant told my mother Pamela, when she was thirty-five and desperate for a baby. In Hunters Hill, a kind of Stepford-upon-Sydney, childlessness was next to godlessness. Especially after a decade of marriage.

It might have been 1968, but there were no outward signs of revolution or even social unrest in the leafy peninsula where the Lane Cove and Parramatta Rivers flow into Sydney Harbour. All that awkward business was in the 1840s, when convicts escaping from nearby Cockatoo Island swam to shore and hid in the densely forested finger of land known as Moocooboola, or meeting of waters, to its original inhabitants. Despite the pill and the war in Vietnam, Hunters Hill was the peninsula that time forgot. John hunted and gathered, while Pam cooked and cleaned. When she wasn’t doing either of those things, my mother attended meetings of the local chapter of the Young Wives club. One hundred years after the publication of Louisa May Alcott’s Good Wives, these young married women were the living sequel to Little Women. But young is a more forgiving adjective for a wife than good. In real life, the one mistake a good wife could not make was that she be infertile. In desperation, Pamela followed the recommendation of her hairdresser, whom she consulted more regularly than any priest, and made an appointment with a clairvoyant.

‘I don’t want you to speak,’ the clairvoyant said when she opened the door to her apartment, decked out in a flowing white caftan. ‘That’s how I do business. I don’t want you to give me any information whatsoever.’

She ushered Pamela inside and they sat down across from each other at a square wooden table in an otherwise sparse room. Natural light seeped through drawn curtains.

‘You have no children,’ the clairvoyant announced, as if it were news to the good wife sitting across from her. ‘Don’t worry about it, dear, you’re going to have two.’

Pamela’s eyes widened. She couldn’t see how that would happen. None of her doctors had ever spoken with confidence about her chances of conceiving.

‘You’re going to have the girl first, then the boy three years later,’ the clairvoyant continued.

Enchanted by the authority of her prediction, my mother never imagined its every detail would come true. More than forty years later, though she struggles to remember what she did yesterday, my mother recalls the prescient woman’s exact words.

‘There’s one other thing you should know,’ she added, with a performer’s gift of timing. ‘Your daughter is going to be very musical.’

2

DO YOU STILL PLAY THE PIANO?

At my twentieth high school reunion, it was the only question anyone had for me. Nobody cared whether I was married or divorced, gay or straight; when I had left my home town of Sydney, or for how long I had lived in New York. The reunion coincided with a trip home, and curiosity about my former classmates got the better of me. I’d had no contact with the vast majority of them since leaving school.

The truth was that I had been widowed more than three years earlier when my husband John died of cancer. I had moved to New York to try to figure out what to do with myself, and I still didn’t have a clue. This wasn’t the sort of self-portrait you could sketch after a quick hello and a you’re looking well, even if you wanted to. Most people—and especially those at a high school reunion—want executive summaries and concise answers. Unanswerable questions and existential dilemmas are anathema to the high school reunion, which relies on pithy anecdotes, funny stories and bad news of former classmates relayed with a dash of schadenfreude. Stories are everything at the school reunion, except when you’ve got the wrong kind to tell. Mine wasn’t the sort of tale anyone wanted to hear, certainly not over a glass of bubbly and a tour of the school’s new science and technology wing. Or perhaps they would love to hear about it, but from someone else—otherwise it would be too much like looking directly at the sun.

I felt pathetic at the preparations I had made to come face to brave face with other faces in their late thirties. I’d carefully applied concealer, which usually lay dormant in the cupboard under the bathroom sink. I’d put on a pair of particularly high heels to optimise the length of my legs, which after all these years I still wished were longer. Why I cared what these women thought about the length of my legs is beyond me. I’d been worried that I would be more wrinkled than my peers, or the only one

without a ring on my wedding finger. And appalled at myself for having those thoughts.

My former classmates and I agreed on the balminess of the October evening, how fabulous we all looked, and how we really were ‘old girls’ now. The regrettable terminology of alumnae put me in mind of livestock trussed up for display. After twenty years, the dynamic remained unchanged: we were still women dressing up for each other.

‘Are you still playing the piano?’ came the first question, from a woman gripping the stem of her champagne flute as if for balance. It wasn’t even 8 p.m. ‘You teach piano, don’t you?’

Taken aback, I said, ‘Actually, I haven’t taught piano in years. I worked in book publishing, then—’

‘Oh,’ she said, clearly disappointed. ‘But you still play, don’t you? I’ll never forget you playing for school assembly all those years.’

For assembly, twice a week for six years. For the choir. For the madrigals a cappella group. For the solo instrumentalists and the aspiring opera singer. I played for anyone who needed an accompanist, and for whoever asked me. The piano was my first love and, from the age of seven, I spent thirteen years studying the instrument and performing classical music, undertaking annual exams and participating in competitions that to this day remain some of my most vivid experiences of success and humiliation.

The onslaught of unanticipated questions from other ‘old girls’ told me it would be a long night, and my first glass of champagne soon emptied. But before I could find the bar, I saw Astrid approaching. Astrid, the one old girl who distilled everything I had loathed about attending an all-girls school. Even now she was olive-skinned and radiant, a mature version of her fourteen-year-old self, who would have won a contest for prize bitch out of a competitive field. As a pale freckled girl whose braces glinted in the unforgiving Australian sun, I would gaze at Astrid from the corner of my eye in longing and despair. Her hair wasn’t a mousy brown, falling straight like water, but a halo of tousled chocolate curls. Her frequent laugh, natural and wide-mouthed, revealed rows of perfect white teeth. She sat in the back row of our classes, at the desk nearest the window, a commanding position that enabled her to monitor events both outside and inside the classroom. Astrid never hesitated to offer an opinion to the teacher, or to answer a question, and being incorrect seemed not to faze her; she would receive news of a wrong answer with a nonchalant shrug, while if I made one mistake I would stew in hot embarrassment for the remainder of the class. ‘Grammar is a piano I play by ear, since I seem to have been out of school the year the rules were mentioned,’ Joan Didion wrote in her 1976 essay ‘Why I Write’. I must have missed the classes on self-esteem. All I knew was that Astrid seemed to understand something about living in the world that I did not. Even now I longed to ask her what it was.

Watching her move in my direction, a huge smile on her face, I became convinced she beamed in the direction of someone just behind me. We had barely exchanged words at school. I couldn’t fathom what she could possibly have to say to me.

‘It’s great to see you!’ Astrid said. ‘How have you been? Do you still play the piano?’

I attempted to steer the conversation in a different direction, but she was having none of it.

‘Yeah,’ she said, ‘I’ve got three kids, can you believe it? But really, I’ve never forgotten you playing the theme from—’ Surely she could not be serious. I knew what she was going to say, and still I couldn’t believe she was actually going to say it.

‘You know, the theme from The Man from Snowy River. You were fantastic! You still play, don’t you?’

In Music classes, waiting for dour Mr Jones to show up, I turned pop-music tricks for my classmates. With the popularity of Billy Joel, Elton John, the theme from M*A*S*H and movie soundtracks, the early to mid-1980s were generous to piano players. The song requested most frequently was ‘Jessica’s Theme’ from the 1982 movie The Man from Snowy River. The film score was so popular that, more than thirty years later, it remains in Amazon’s top fifty soundtracks of that decade. Allegedly ‘Jessica’s Theme’, my signature tune, was partly responsible for a subsequent generation of little Jessicas.

I wasn’t the only teenager with a hopeless crush on the film’s star, Tom Burlinson, who plays Jim Craig, an intelligent but poorly educated horseman from the remote high country of rural Victoria. He’s in love with Jessica, the headstrong daughter of his wealthy landowner boss. Played by Sigrid Thornton, Jessica fulfilled my fantasies of what rebellion against one’s parents looked like: to sit at my piano while dreaming of travelling the world, and to retreat each night to my bedroom after a home-cooked meal to read a novel. Jim and Jessica’s romance is as practicable as that between any teenagers with little or no income, but I would have had to remove my rose-coloured glasses to see that, and at thirteen mine were affixed permanently to my face.

In the school’s political hierarchy I occupied a neutral, if isolated, position. Friendly enough with most of the girls in my year but not a fixed member of any one faction, I was a social Switzerland. Away from the piano, many of the other girls may rarely have given me the time of day, but my ability to reel off popular songs and sight-read—to play a piece of new music at first sight—put me beyond the brunt of their forensic criticism. Because of the piano I enjoyed a level of immunity from the social persecution that the coolest girls perpetrated on other awkward saps who lacked the protection of an instrument.

Twenty years later, I was astounded to realise that despite feeling like the world’s biggest nerd at the time, I had earned their admiration and respect even though I could neither see nor enjoy it.

My school reunion turned into a recital of the popular songs I used to play by request before and after Music classes. A chorus of mature women sang out song titles with startling recall: ‘Jessica’s Theme’, the theme from M*A*S*H (‘Suicide Is Painless’) and an Elton John medley. They also remembered me as quite the Billy Joel interpreter, wrapping my still-small hands around ‘New York State of Mind’ and ‘Allentown’. I had played those songs repeatedly, dreaming of living in New York one day when I didn’t have to get up at six every morning before school, or rely on my mother to drive me around. I had no idea what a New York state of mind might be, nor where Allentown was, or why they might have been shutting down the factories there. Though I learned that Allentown was in New Jersey, it might as well have been New Zealand for all I understood about the place. Had everyone else been as oblivious as I was to the irony of my performing songs about creative melancholy and job insecurity while in the cloistered protection of a private girls’ school?

After The Man from Snowy River shot him to stardom, Tom Burlinson acted in several films before carving a successful career from singing and musical theatre, with a specialty in impersonating Frank Sinatra—when I, as a thirteen-year-old with an imperfect understanding of the relationship of one’s life to the plans we make for it, had expected him to become a major movie star.

At the reunion, my peers did not see my bookish 37-year-old face but that of the musical teenage girl, frozen in time beside the assembly-hall Steinway. I was as guilty as anyone of fixing in my mind an image of a girl who in many cases bore no relation to the woman in front of me, reeling off her personal and professional statistics as though I was a census collector.

Yet I was struck by the similarities in my peers’ life stories. They put me in mind of another famous statement of Joan Didion: ‘We tell ourselves stories in order to live.’ I learned that a demographically disproportionate number of women had borne three children. That an even higher number lived in the suburb in which they had grown up. And that many had worked for one employer for more than ten years. We tell each other stories in order to live with ourselves, is more like it.

After John died I had yearned to be far away from everything comfortable and familiar to me, so at the reunion I stuck to my story that I had moved to New York after being widowed. But as these conversations confirmed, the truth was, with or without my husband,

I never could picture myself living their sort of life. The idea of working at one place for a decade did my head in, as did the idea of moving back to live in Hunters Hill. No wonder they all expected me to still be sitting at the piano. And children? Despite my grief as a young widow, I was quietly relieved John and I had never had a baby. My perception of parenting, forged in a house devoted to routine and repetition, was limited to a daily grind of dirty nappies, endless laundry and thankless meals.

On the other hand, the reunion forced me to see the tangible benefits that accrued from the routines and the repetitions that my former schoolmates described with wabi-sabi smiles. A stable income. A family life. Enduring love, or whatever describes the glue that binds a couple after years of childrearing.

I thought of the line about apples not falling far from the tree. I had come to the reunion looking in vain for other apples that had scattered far and wide, and that had suffered a few bruises as a result. My mistake had been to expect difference, not repetition. I now see this was an unintended consequence of my grief, which in its voracious need for disruption had led me to change country, career, and the way I chose to work and relate to people I loved: via Skype. Though the remoteness was largely of my own making, I felt as distant from these women at thirty-seven as I had at seventeen.

Almost everyone I spoke to that night had been certain that I must have been ‘doing something with the piano’ for the past two decades. To them, I had been working as a musician, not as a book editor. I felt sorry to disappoint them, and bewildered by their surprise at how differently my life had turned out from what they’d expected. Hadn’t theirs? Frankly, the way my life had turned out was a surprise to me. I had not planned to be in my late thirties, trying to improvise a life as a widow—and a self-employed one to boot, cobbling together bits and pieces in what has come to be known as the gig economy. That was the only sort of gig I played these days.

Girls at the Piano

Girls at the Piano