- Home

- Virginia Lloyd

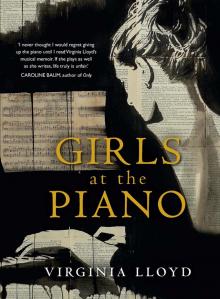

Girls at the Piano Page 3

Girls at the Piano Read online

Page 3

I glanced at my mother across the kitchen table to read her face. She always sat in the same position, the north to my south. To be geographically accurate it was the other way around, but my sense of direction was then as undeveloped as the rest of me. From the way my mother briefly pressed her eyes closed and remained tight-lipped, I knew that she didn’t want to go either. Of my mother’s silence I heard every note.

After what felt like two hours we parked outside my grandmother’s self-contained cottage, one in a row of identical blood-red brick dwellings. It wasn’t far from the Padstow water tower, which looked like a UFO that had been covered in concrete to hide the bleeding obvious. My grandmother’s relocation from Yeoval, a small town in the central-west of New South Wales, had not been by choice. My younger brother and I clambered out of my father’s car. Arriving meant we were closer to the halfway point of our round trip.

Alice Lloyd opened her front door and stepped onto the tiny concrete landing. Despite her scuffed house slippers and her flesh-coloured pantyhose, thick enough to floss with, she effected a regal air. She waited for us to ascend the four steps to greet her, with the solemnity of Queen Elizabeth standing on the terrace at Buckingham Palace.

‘Go on, say hello,’ Dad said, urging me along the path towards her. At the car my brother clung like static to my mother’s skirt.

On the landing I stood on tiptoe to give the old lady a kiss. When she brushed her lips against my cheek they didn’t purse together or make any sound. Her greyish-white whiskers tickled as I inhaled the tobacco on her clothes. Instead of a hug she gripped my shoulder with one hand so that I could feel each bony finger. She scared the hell out of me, but I had no choice but to follow her inside, where the kettle was invariably on.

By the time the rest of my family joined us, a pot of tea ensconced inside a crocheted cosy sat on the kitchen table like a caffeinated Trojan horse. ‘I’ll be Mother,’ Alice said, standing to pour the strong black tea into floral-patterned china cups.

As Alice handed them out, each cup trembling slightly in its matching saucer, my eyes locked on her stained fingertips. Dad had explained that their dull mustard-yellow tinge was because she rolled her own cigarettes, but I didn’t understand why you would waste time rolling cigarettes if your aim was to smoke them.

‘Tell Granny your news,’ Dad prompted.

Embarrassed, I said, ‘I started learning the piano.’ There was no piano inside her cottage, even though Dad was always telling me how his mother had taught piano when he was a child. And I knew my father was adopted, so it wasn’t as if I was carrying on a family tradition by learning to play. But I could hardly bear to disappoint my parents. They had been married for eleven years before I showed up. From the moment of my late arrival, my job was to be agreeable at all times.

‘The pianner?’ Granny’s bushy white eyebrows shot up above her thick glasses. ‘That’s good,’ she said, firing off an unexpected smile. She took a sip of tea and sucked at her false teeth. ‘You know, the most important thing is to practise.’

A ticking wall clock punctuated the uncomfortable quiet that descended. Economy was a defining principle of conversation around the dinner table at home, and I understood there would be nothing further now. My father smiled at me and gave my leg a reassuring pat. He was disappointed, but perhaps not surprised. Neither he nor his sister, my aunt Charlotte, could play the piano. Their mother had taught other people’s children, but not her own.

When Alice died eighteen months later, in the winter of 1978, Dad took us on a long road trip to Yeoval. Those approaching via the Great Western Highway encountered a sign that announced the entrance to ‘The Greatest Little Town in the West’. Even then I regarded the claim with scepticism. The giveaways were the bullet holes riddling the metal placard and the absence of people. Long tufts of sun-bleached grass waved from lonely crossroads. Dilapidated wooden fences enclosed paddocks of wheat. The doors of a miniature weatherboard church were padlocked in a gesture more hopeful than defensive, with the most recent estimate of Yeoval’s population a tiny 293. The town resembled the abandoned set of a B-grade western.

Yeoval’s sole claim to fame is as the place where Andrew Barton Paterson, better known as Banjo, spent his first five years in the late 1860s. He grew up on Buckinbah Station, a sprawling property that named the original township. In 1882, when Buckinbah was renamed as Yeoval, the young Paterson was working as an articled clerk for a Sydney law firm as a recent graduate of the prestigious Sydney Grammar School. It was another three years before poems under the name ‘Banjo’ began appearing in the Bulletin, which first published his best-known work, ‘The Man from Snowy River’, in 1890.

Adopted soon after his birth in 1934, my father grew up on a small wheat farm amid plagues and drought, with loving parents who pinched every penny. He made his pocket money by skinning rabbits. At times, he said, so many rabbits covered the ground that ‘it looked like the earth had got up and walked’. Eventually his family left the farm and moved into a single-storey dwelling in Yeoval proper, where his father George Lloyd took over a stock and station agency selling everything from farming machinery to fresh eggs.

From the back seat of my father’s car I stared at the forlorn weatherboard house, for which modest was too modest a word. In summer they must have baked like bread inside it. The house looked both authentic and makeshift, like a forgotten display in a museum of disappointment. I could hardly conceive of anyone, let alone my father, living in it—or turning up on its drab doorstep for a piano lesson with my terrifying grandmother. It wasn’t much, but to Alice I suppose it hadn’t been much for more than thirty years.

Between my mother’s general impatience with my father’s trip down memory lane and my ongoing sibling skirmish in the back seat, we did not dwell long on the sorry sight. Owing to the heat, the dust, the sense of desolation, and my horror at Dad’s stories of rabbits and locusts, it was on that rural tour that I came to associate living in the country with the Old Testament.

A few years ago I found myself once again travelling with my parents to visit an elderly woman on the outskirts of Sydney. This time it was my aunt Charlotte, my father’s sister, who lived on the city’s rural fringe. Over three decades, undulating fields where sheep and cattle had safely grazed had become purpose-built enclaves of identical single-level houses on quarter-acre blocks. We sat down before the pot of tea that remained as essential at family gatherings as the cup of wine at Communion. We had just returned from a visit to the house next door, where my sixty-year-old cousin Bronwyn, Charlotte’s daughter, lived alone. In an architectural echo of the notion that women grow up to look like their mothers, the two houses were exactly the same on the outside, though their interiors differed in layout. The collective glassy stare of my cousin’s porcelain dolls, which sat in rows on her living room wall, gave me the creeps. They looked like something out of a horror movie—the replication of a notion of beauty from an era when an intact hymen and the ability to play the piano, rather than a trust fund and an MBA from Harvard, represented ultimate social value. Rosy-cheeked maidens sat shoulder to shoulder in long silk dresses of block pink, lemon, mauve and the inevitable white. All dressed up and nowhere to go, they gazed into a future that would never materialise.

Sipping my tea at Charlotte’s, I couldn’t decide which was more distressing: the size of Bronwyn’s doll collection, or the fact that she lived next door to her parents.

Toward the end of the first cup, Charlotte leaned on wobbly knees and slowly stood up from the table. ‘I’ve got something to show you,’ she said as she ambled in the direction of her sewing room. In years gone by this sort of threat announced the imminent bestowing of a homemade tapestry to hide in a drawer when I got home. Now in her late eighties, my aunt had discovered the internet and enthused ad taedium about branches of the family tree she had collected during her genealogical research. The room that had once been dedicated to sewing and painting-by-numbers was now the headquarters of Charlotte’

s investigations.

To my surprise, my aunt returned clutching a bundle of documents relating to her mother’s musicianship. In April 1912, at the age of sixteen, Alice May Morrison Taylor attained her Elementary Certificate by passing examinations in Musical Memory, in Time, in Tune and in Sight Singing, then the Intermediate level just five months later. In florid script the Intermediate Certificate announces that Alice has fulfilled the Tonic Sol-Fa College of Glasgow’s requirements for Reading Music at First Sight, and Writing it from Ear, and of eligibility for an advanced Choir. In between these achievements, she passed her First Grade examinations in Staff Notation (the ability to write music) in May 1912, and claimed her Elementary Certificate in Theory of Music the following January. There were references to her public appearances and letters of recommendation for her employment as a choir mistress. ‘She is a very painstaking and enthusiastic musician and I have great pleasure in recommending her for any important appointment she may seek,’ wrote her teacher, the esteemed local musician Frederick Hervey, less than two years later. Alice had been a late bloomer but a fast learner.

I found it difficult to believe that the subject of these certificates and glowing recommendations was the same woman who, one decade on, battled rabbit plagues and endless dust on a wheat farm in the middle of Nowhere, New South Wales. It was impossible to reconcile the evidence of a very musical girl with the family story of a humourless woman with a matching chip on each shoulder. With the wife who recorded local marriages on her kitchen calendar so she could determine, by the birthdate of the couple’s firstborn, which weddings had been shotgun. With the mother who delighted in the Christmas gift of a cardigan from her son until she discovered that her daughter-in-law had selected it, when it became unsuitable and had to be returned to David Jones.

In an effort to prompt kinder memories of my grandmother, I dug out some old photo albums from the closet in my parents’ house that served as the family archive. The Alice pickings proved to be slim. A couple of fading colour snaps from the 1970s capture her as a kind of human scarecrow, all fuzzy grey hair and rakish frame.

One of them depicts the two of us mid-slide on the uncomfortable black leather couch in the living room of the house I grew up in. Alice is wearing a blue and white floral print dress, and black old-lady rubber lace-up shoes—which, apart from the house slippers, were the only things I saw on her feet. I’m in a signature sprawl, one matchstick leg flung out in front of me and the other over the side, a book in my left hand and my right thumb in my mouth. Between us lies the naked body of my doll, Gail.

Gail was an unlikely gift from one of my father’s acquaintances in the building trade. Until I met her I had exhibited no interest in dolls, but I had fallen hard. Wherever I went, Gail went too—including a swimming pool, which transformed her black nylon tresses into a triangular lump. Soon after that, her head was somehow divorced from her torso, so she became less than half the doll she had been; in an enduring family mystery, her body was never seen again. Gail’s dismemberment only made me love her more. Her head accompanied me everywhere. At night I spread out her matted inky halo on my pillow and laid my own head of thick brown hair upon it. I loved feeling those soft acrylic lumps against the cool silkiness of my hair. Lying in bed, my face pressed up against Gail, was the only time when my hair was free. My mother loathed freely flowing locks on any woman, but particularly on her daughter. She insisted that my hair be harnessed in either a ponytail or pigtails so tight that they never had to be redone.

In the photograph Gail was yet to lose her torso. It’s my only photo of her intact, and until recently its primary value was as the poignant Before shot of my beloved confidante. Looking at the picture again, I noticed a lot of space between my grandmother and me on that couch. Who can say whether she had been reading to me or if I had been trying to read to her—or perhaps to Gail.

Reading is something I associate with my mother, who drove me every week to the Gladesville Public Library to replenish my Holly Hobbie drawstring book bag; who read stories to me until I grew old enough to read them for myself; who volunteered to help other children at my school learn to read. Who, though she was in an almost constant orbit, shuttling between the kitchen and laundry, the clothesline and the bedroom, the school and the supermarket, could always be found, in her rare moments of stillness, with a magazine or newspaper in her hands.

Because of my intense attachment to Gail I identified strongly with Christopher Robin’s utter dependence on Pooh in When We Were Very Young and Now We Are Six, which my mother had bought for me and which I obsessively read and re-read. It wasn’t only the rhymes of the poems and their exotic locations that enchanted me. Christopher’s melancholy sang to me from the creamy illustrated pages, and I longed for the kind of solitude in which a poem might present itself for me to write down. In A.A. Milne’s world, children visited Buckingham Palace and scolded their nanny and sat quietly on their favourite step. No one interrupted their daydreaming to ask what they were doing or to remind them that dinner would be ready soon. How marvellous to write poetry like Christopher, I would think. But no sooner had I started down that path than I tripped over a large stumbling block that seemed impassable: what would I possibly write about? I had no step of my own, no nanny, and no chance of visiting Buckingham Palace. Who would be interested in poems about a little girl and her best friend, Gail? And with Gail now just a head with matted black hair, any hypothetical illustrations would have been a sticking point, too.

My favourite books featured a heroine solving a mystery. The escapades of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five and Secret Seven. The neighbourhood adventures of Milly-Molly-Mandy. The Nancy Drew detective stories by Carolyn Keene, Julie Campbell Tatham’s tales starring Trixie Belden, and later Agatha Christie’s elderly sleuth Miss Marple. Together they formed a genealogy of investigative heroines. The puzzles they encountered were inevitably solved by the last page. Their every story had a positive ending; every problem, a neat solution.

But now, as I reviewed the certificates and correspondence relating to my grandmother’s musicianship, I realised that Alice’s story remained a mystery to me. What had happened to lead her in the opposite direction—geographically and professionally—of the one in which she’d seemed headed? Why had she given up a burgeoning professional life in music in Glasgow? How could she pack up her talent and experience and sail to Australia, only to settle for life on a farm?

Was my grandmother’s altered relationship to music a result of financial circumstances, boredom, disappointment—or something else? Had the relentless Australian sun bleached her of her passion for singing? If not, where did she channel her emotional attachment to music? What did it mean to lead an early life in which music had been central, only to give it up like an impossible love? I had done this myself, throwing away thirteen years of intensive piano study for a professional life that had no music in it. What had each of us gained in doing so—and what had we lost?

My grandmother’s brief career in music was a tantalising and inexplicable development. The few odd pieces of Alice’s puzzle that I possessed formed no coherent picture; instead, they created a portrait defined by what was missing. Suddenly I felt pulled toward Alice by what little I knew and an urgent desire to find other parallels between our experiences as musical girls. I wanted to use her scant biographical record to explore these parallels, and the ways in which our experiences reflected those of other girls drawn from the pages of history and fiction—aristocrats and spinsters, entrepreneurs and writers—who had sat at the piano over the course of its history. I came to believe that setting aside Alice’s frightening mask of old age might help me to understand my own voyage around the piano—and help me to find my way back.

4

MY FIRST PIANO WAS A BABY GRAND. I loved the instrument’s glossy black lid, the clink of its metal keys, and the way it was light enough for me to tuck under my left arm. It would definitely have been the left arm because at five years of age I sucked my right

thumb with a degree of attachment that not even my favourite toy could compete with. Security Is a Thumb and a Blanket, according to Peanuts comic-strip creator Charles Schulz’s book of the same name. There must have been something to his claim because the book outsold two volumes on the John F. Kennedy assassination to become the second biggest-selling book of 1963.17 But blankets were for babies. For me, security was a thumb and a miniature piano.

The only toy pianist—or any kind of pianist—of my acquaintance was Charlie Brown’s friend Schroeder. We seemed to be around the same age but judging by his technical facility Schroeder must have started playing as soon as he emerged from the womb. I was encouraged that he could produce such exquisite music from his instrument, because it was exactly the same shape, colour and dimensions as mine. He was so good that he hardly ever referred to printed music and never needed to practise, and yet he practised all the time. It was from the blond boy-genius that I learned to crouch at my toy piano: back bent over, shoulders hunched up around my ears, legs crossed, fingers dropping from my hands held high and close together like pedigree paws.

Schroeder’s appearances were the second-best thing about the Peanuts comics and television specials, which I watched sitting on the olive-brown linoleum floor, Gail’s decapitated head in my lap and my thumb in my mouth. Above Schroeder’s voluminous golden hair a series of black squiggles and lines and symbols sometimes materialised. Despite having never seen written music before, I understood that somehow the lines and dots represented the sounds that Schroeder produced at his toy piano. Did he know what each dot and line meant? How had he learned that? I watched Schroeder’s little fingers chase each other all over the keys as the score—which Charles Schulz faithfully transcribed—keeps pace with him, one or two bars at a time. It seemed both beautiful and incredibly difficult.

Girls at the Piano

Girls at the Piano